It was The Roaring Twenties and Manhattan was bursting with creativity and a new found sophistication. Noticing an unpleasant increase in traffic congestion that accompanied the accelerated pace, a prominent real estate developer named Fred F. French conceived a plan for a high-rise, residential development. It would be nestled around a centrally placed, tranquil park, replete with amenities and services, and tailored to the needs of the middle class men and women flocking into the city each day. Its most compelling attraction? They would easily be able to walk to work in midtown.

French came from a poor New York family, but his mother was well educated and valued schooling. Bright and adventuresome, he won scholarships to Horace Mann H.S. and Princeton University. He dropped out of Princeton after only one year and embarked on a cross country odyssey, supporting himself by digging ditches, working on the railroad, cowboying and mining. When he finally came back to New York he got into construction after an engineering course at Columbia.

French needed financing to get his real estate vision off the ground, and everyday methods just would not do for him. So he devised the French Plan, which allowed ordinary citizens to buy stock in his development plan, receive dividends and share in the profits. Money poured in following an aggressive advertising campaign and he proceeded to secretly buy up the old tenement buildings that then occupied the escarpment overlooking First Avenue between E 41st and E 43rd Streets. Most of the land was purchased before the former owners realized they could hold out for a higher price. When the buying frenzy was over there was only one targeted building that remained unsold. It would find itself surrounded by tennis courts until it too finally was sold in 1956, when the last Tudor City building went up.

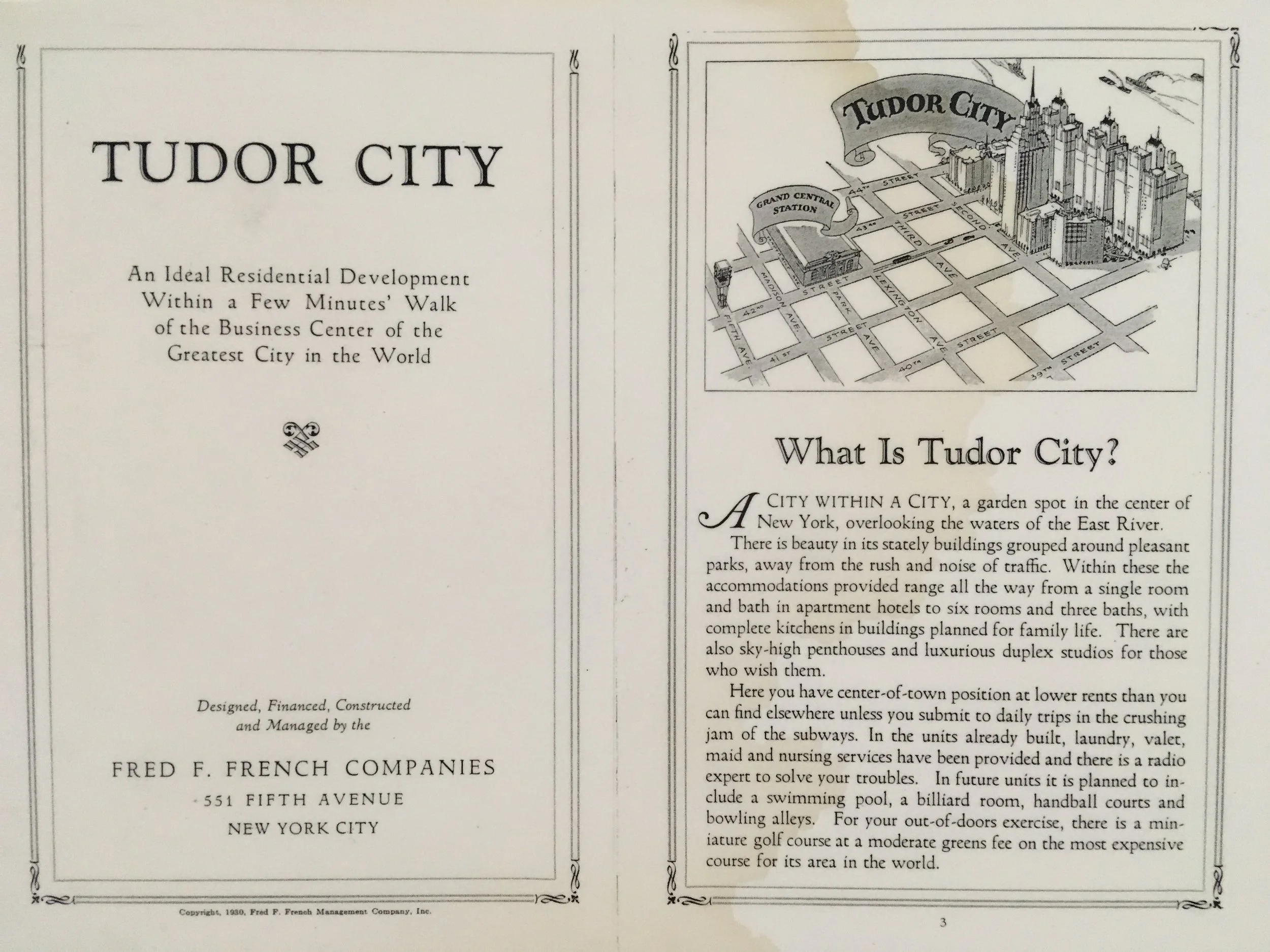

The location was selected with great foresight. Centrally located, it was also a transportation hub with easy access to Grand Central Station and the Second and Third Avenue Els. The escarpment rose majestically above 42nd Street, which disappeared into a tunnel east of Second Avenue and reemerged on the other end near First Avenue. Since the Tudor style was popular for homes being built in the suburbs. French decided it would be just the thing for his in-town residential development.

In order to lure prospective residents French wanted to provide all the amenities of suburban living. The parks were central to his plan. While many grand residential buildings of the time were built around garden courtyards, French turned the convention inside out in Tudor City by placing the green spaces on the outside and orienting the buildings toward them. Tudor City, as is famously quoted, turned its back on the East River, which was an industrial area of slaughterhouses and barge landings, all dominated by the coal-burning Con Edison plant. The pastoral tranquility of the parks were a welcomed relief from the noise and pollution along the river. They contained arbors and gazebos, fountains and tree-shaded walks, and an 18 hole miniature golf course with lighting for evening play. Tudor City was a success, and it’s buildings were renting out faster than they could be completed.

French died in 1936 but the firm he founded continued to own and manage the properties until 1972, when the Helmsley-Spear company bought Tudor City. A relentless battle by residents ensued against Helmsley’s plans to build giant skyscrapers on the open spaces. It all came to a head when a bulldozer rumbled down Tudor City Place at 6 AM on the Sunday morning of Memorial Day weekend in 1980. An alert resident saw it coming and sounded the alarm. People poured into the street and under the leadership of community leader John McKean, blocked the bulldozer from entering the parks and then managed to secure an injunction against the planned destruction. Helmsley finally accepted defeat.

In 1987 Tudor City was sold to Time Equities, Inc.. As it undertook the conversion of its Tudor City buildings to cooperative ownership, Time Equities demonstrated its understanding of the importance of the parks to the community by donating them to The Trust for Public Land, a national conservancy organization dedicated to the preservation of such open spaces. The development rights of the parks were extinguished, which effectively eliminated any possibility of future development.

Tudor City Greens, Inc. was formed in January 1987 for the purpose of assuming ownership of the parks from The Trust for Public Land. In exchange for this transfer of ownership, The Greens granted an easement to The Trust that prohibits construction and bans unacceptable behavior in the parks.

The parks had suffered long years of neglect when Tudor City Greens took on the task of bringing them back to life. A Master Plan was developed in 1988 to guide the work. Improvements have included: adding new electricity and an irrigation system; repairing existing lighting and installing new lampposts; repairing sidewalks and upgrading and reconfiguring pathways to create new gathering areas; restoring the original wrought iron fencing and manufacturing new fencing where needed to replicate the original, and providing new bistro chairs and benches and posting new park signage. Unhealthy trees and shrubs have been culled, soil quality restored with the yearly addition of fertilizer and mulch, and new plantings have been undertaken. All has been done with great care to preserve the urban nature of the parks and keep them in harmony with Tudor City architecture.

Looking toward the future, in 2001 Tudor City Greens commissioned a team of professional garden designers to create a new Master Plan. This provides an overall blueprint for new and replacement garden structures and amenities, plantings and any other needed improvements.